Emerging from Sydney’s vibrant underground, Thunk Recordings was, for a brief yet important moment, one of the most seminal labels in electronic music. Founded in 1996 by Brett Mitchell (Earthlink), Phil Smart and Timon Marmion, Thunk became a vital platform for local producers like Pocket and Head Affect, who were pushing a unique style of futuristic dance that melded house, breakbeat and indie influences.

It was also a true DIY endeavour that eschewed industry norms and embraced digital disruption to showcase what became known as the ‘Australian sound’ to the world. The label released some of Infusion’s early works – a band that would go on to become one of our most celebrated electronic exports – and garnered support from international DJ heavyweights such as John Digweed, Sasha and Hernan Cattaneo.

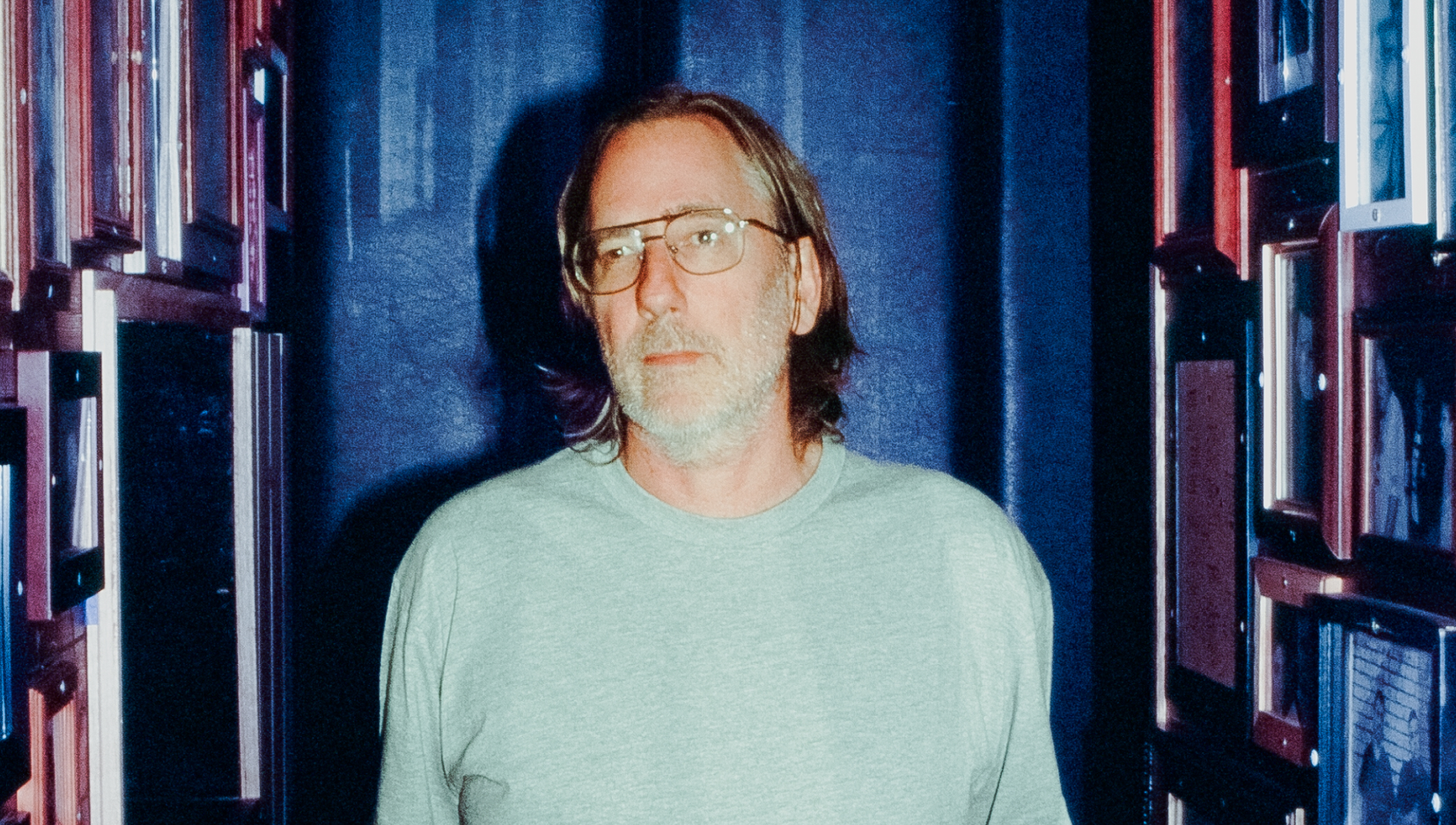

Since mid-2024, the once vinyl-only imprint’s catalogue has been undergoing a digital reissue, connecting a new generation of music lovers to a time of sonic innovation. Here, Phil Smart looks back on the era of Thunk – a label that put Aussie dance music on the global map.

Hi Phil. Can you tell us about the genesis of Thunk Recordings? What inspired you, Brett and Timon to launch the label?

I met Brett in ’94 and we started making music together, beginning with some ambient music as Altitude. We knew some other electronic musicians creating similar ambient material and we naively thought… ‘let’s find some more people and put together a compilation’!

So we started a label called Think and released a compilation album of antipodean ambient music called Environments in 1995 and got a distribution deal with Shock in Melbourne to get it out there. It got released internationally and sent to a bunch of overseas DJs and media and got a great response, at a time when ambient music was experiencing quite a peak, which encouraged us to go on to create and release Environments 2.

At the same time, we were also producing club records, and again we knew a lot of people around us like Pocket, Infusion and Head Affect making great music that we loved, so we started a dance offshoot of Think called Thunk.

One of the reasons we could even start these labels was the realisation that we had all these newly available digital tools that enabled us to do many of the things that you needed to do to create a label much easier than before, not only making the music itself but also things like making artwork, mastering and communications via email etc.

“A common thread between many of the artists was a love of bands like Depeche Mode and New Order.”

Was there a particular vision for the label? An overarching sound or ethos you were trying to achieve?

We really just wanted to get our music out there, as well as that of our friends. We wanted to represent our own Australian sound and do our own thing, which is why the Thunk stuff sounds unique. Some of it has guitars and other rocky elements that most of us grew up with and it had the spirit of indie music culture infused in it. We also liked to experiment with what dance music could be, and if you listen through the back catalogue you’ll hear a bunch of stuff from a stage some of us went through of making tracks in 12/8 or 6/8 time signatures.

The sound I would describe as progressive house and/or tech house, in the original meaning of those terms, with a bit of indie, rock and new wave influences thrown in. A common thread between many of the artists was a love of bands like Depeche Mode and New Order. It also had a strong influence of U.S. West Coast breaks and West Coast house, partly influenced by my travels there and some of the guest DJs we brought out for Sabotage and Tweekin, like Scott Hardkiss, DJ Dan and Terry Mullan and well as London tech house players like Mr C from The End. It was also responding to the progression in house music globally and techno particularly from Germany and Detroit.

What kind of an impact did Thunk have on the global clubbing scene and who were some of the label’s biggest supporters?

I think it showed the world that quality music was coming out of Sydney, remembering that at the time, the rave scene didn’t have the total global profile that it does today, thanks to the ubiquity of the internet.

We got an Australian sound out to the world and it was well received as well as being different, particularly in places like the UK. We licensed the first release to a UK label, which was encouraging and validated that we were onto something and on the right path.

Big supporters were people like John Digweed, Sasha, Dave Seaman, Hernan Cattaneo, Adam Freeland, Phil K, Anthony Pappa, Stephen Allkins, the Hardkiss crew and many other West Coast DJs.

Thunk was home to some of Infusion’s early music. How did this come about?

We just knew them as friends who were making great music and doing similar things, going to the same parties and clubs. I’ve actually known Frank [Xavier] since he was a kid running around my friend’s studio in Wollongong when I was at uni there, as my friend was dating Frank’s sister, so the connection goes back a long way, and we even still play together occasionally at 77.

“It was a lot harder to run a record label in those days, especially being located on the other side of the world from the dance music hotspots.”

How did Club 77 play an integral role in Thunk Recordings?

Club 77 was the second home to most of the main Thunk artists. It’s where the crew hung out on Friday nights at Jus’ Right, then Tweekin. Then there were often other parties at the club on a Saturday night that we’d either be playing at our just go to, and a lot of us would also go to Club Kooky on a Sunday as well. So we were all influenced by the music that was played in the club across a range of nights, as well as the community that developed there and regarded it as the closest thing we had to a church or temple. Many of the acts played there live or as DJs, and there’s even a remix on the first Earthlink EP named after Kooky.

It was also the place that we used to road test tracks that we were making, first playing them off DAT tapes, and then at some point we got one of those Denon rack mount CD players with the pitch control and nudge buttons. That was a game changer, as we could mix down a track on Friday afternoon, burn it to CD and play it in the club that night!

What did running an underground dance label teach you about the music industry at that time?

It was a lot harder to run a record label in those days, especially being located on the other side of the world from the dance music hotspots. Both Brett and Tim had experience already with the record industry though, particularly Brett through his involvement as a member of pioneering Australian electronic act Boxcar.

But it did give us a lot of insight and experience with the whole pressing and distribution process of making physical records, as well as dealing with DJs and promos, record licensing, mastering specifically for vinyl, production, artwork development, and marketing. The whole gamut really.

All good things come to an end and Thunk’s journey drew to a close in 2002. What was the reason behind that decision?

I left at some point toward the end of the 90s as I was overseas a lot and had too much on my plate, and the other guys continued for a few more years before finally winding it up. In the meantime, Brett had moved to New York and Tim went to Silicon Valley so at some point Thunk just stopped releasing records - it was never really a conscious ending.

At the same time, it was the era of Napster and illegal downloading that was the beginning to kill the traditional music industry model. The writing was on the wall and there was scepticism around the future viability of independent record labels.

It’s one of the main reasons that we stopped releasing music through Junkbeats, another label I was involved with in the early 2000s while I was living in Byron Bay. We would put out a track and the next day it was available for free on a Russian download site!

What inspired you to ‘resurrect’ the label by re-releasing the back catalogue digitally?

The main trigger was the amount of people who kept asking us about how they could listen to or buy Thunk music, as it just wasn’t available digitally.

It was also the fact that there was a lot of interest from current DJs, particularly in the first Earthlink EP, which ended up being licensed for a repressing on vinyl by a Berlin label a few years ago after three separate labels asked us about a re-release.

Then there was the idea that we wanted to archive it for posterity in the digital realm, and just get the music back out into the world and available for people to listen to easily again.

Can you select three key records from the Thunk catalogue and why they’re pivotal releases?

Earthlink’s Spectral EP, because it was the first release and because it still gets played to this day, enjoying a second life of late.

Infusion’s Spike, because it was a huge record that got a lot of support around the world and was probably the most played Thunk track at Sabotage and Tweekin.

The Inbred EPs, where the four main artists all remixed each other, because it was heaps of fun, I’ve never seen it done anywhere else in quite the same way, and because it gave us some really amazing remixes!

Do you see Thunk’s influence in the current global scene, perhaps via some of today’s producers, labels or DJs?

It’s funny, I sometimes hear tracks and think it sounds like a Thunk record, especially these days, as people have been referencing the sound of the 90s a lot in modern productions.

Anything else you’d like to mention?

We’ve re-released half of the Thunk catalog so far, with the rest to come later in the year. In the meantime, we are about to re-release the two Environments compilations so stay tuned for that!

You can check out more info on Thunk Recordings and listen to the music via Thunk's Website, Facebook, Instagram and Beatport.

Catch Phil Smart this Saturday July 05 at Club 77, all night long from 10pm til 5am. See full event information, register for free entry before midnight via guest list, or purchase $10 early bird tickets via Resident Advisor.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.webp)

.png)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)